One of my previous articles covered character feel in the first person games, but any talk about FPS genre is impossible without mentioning of the PC platform. In this article, I’m going to share my experience of designing (and adapting) of the PC user experience (mostly for big AAA games).

What is a good PC version?

Let’s define first what is a “good” PC version:

- First and foremost, it’s performance. If “optimization” is bad (whatever players mean by this term), the quality of other features may not be important. And vice versa – the players can forgive you a lot, if they like the game, and it runs well on their PCs.

- Seconds part is controls on PC, which should be at least on “OK” (playable) level.

And that’s basically it. I could’ve ended my article here, but we want more, right? We want our game to be great, not just “good”. And that’s what this article is about.

User experience that is specifically tailored for PC is what make a difference between “bad port” and great PC game.

And first thing that I’d like to start with – If you’re PC game, act like a PC game.

Act as a PC game on the PC platform

PC as a platform has its own set of conventions, some of them, pretty different from the consoles. And PC version of the game should look like it was developed for the PC platform from the ground up, as much as it’s possible.

Main Menu First

On PC, the player is used to change options before any actual gameplay (especially, video options).

The first thing after logos/intro should be the main menu (and not an 1-hour long first user experience without ability to change the performance settings of the game).

There should be an exit!

As much as you want your player to stay in the game, don‘t forget about „Quit to desktop“ button. It may sound funny, but I’ve seen more than one PC port without ability to leave the game.

There should be an exit from your game!

It’s not a fixed frame

The game on PC do not live in a fixed frame: the player can hide your game, can switch to another app, can change the resolution and window mode. Think about it in advance and design a predictable way, how the game should behave in such cases.

One of the simplest tests you can do is just try to Alt+Tab your game, and see if it’s going to crash or freeze (or show any other abnormal behaviour). Surprisingly, many bad PC ports do not pass this test.

There is a life audience outside 16:9

Roughly 10% of PC players have non-16:9 monitors (16:10/21:9 in most cases). Even if you game doesn’t fully support non-standard aspects, it will be launched on widescreen monitors anyway, so you need to design a predictable way, how the game should work with non-16:9 aspects.

The list of common monitor aspect ratios you may consider (numbers are very approximate and may change with time):

- 16:9 (85-88% of the audience)

- 16:10/21:9 (10% of the audience)

- 5:4, 4:3, 5:3 (1-2% in total, but some player can still have such monitors)

- Multimonitor (a special case which requires its own design approach)

It’s not a fixed environment

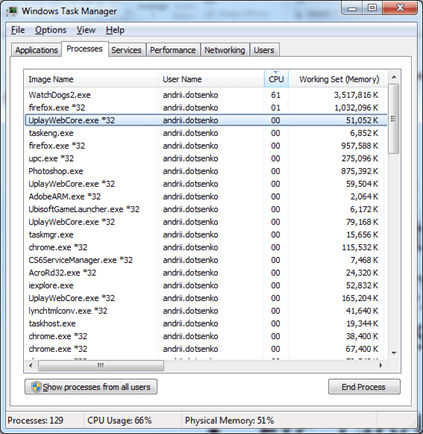

Your game will fight for CPU time with all other software running on your PC:

- You may have the game launcher running, sometimes, more that one (e.g. Steam, Uplay, etc.).

- The player may run a 3rd party software that changes the game (some player like to use things like re-shade or sweet fx).

- The player might have an antivirus that can block some functions of your game.

- You might use an anti-cheat software (which, for example, might not like the 3rd party software the player is running, even if this software is not *technically* cheating).

- Some hardware vendors may run their own 3rd party software that is causing the issues (for example, on Watch Dogs 2 PC, one such software was tracking all the player input, and was so invasive that it was triggering the anti-cheat system).

- All this software may also interact with each other (or may not when it should, which sometimes even worse), and you have very little control here.

The Key PC Difference

Let’s talk about the key PC difference, as a platform.

Which is the mouse. For PC player, the first expected way to do any action in UI is the mouse (not the keyboard).

I‘ve seen it a lot during PC playtests – if the player can finish a task with the mouse, it will be the first reaction (even if the hotkeys are available).

That’s how I came up with a concept of Mouse-centric UI:

PC player should be able to finish any action in the UI, using only mouse.

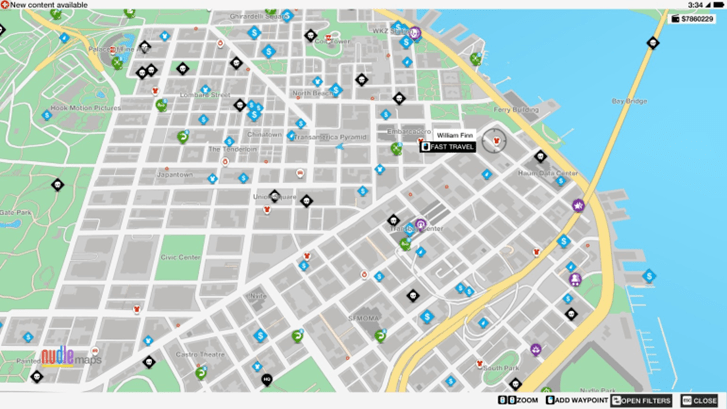

Good example of it is Nudle Map in Watch Dogs 2 PC: it has free cursor, drag & drop navigation, adaptive tooltips, additional menus that can be accessed with the mouse, and even zooming mechanic that works exactly like Google Map.

Let’s look at this approach in more details.

You will need the mouse cursor

First thing that you’ll need for mouse-centric UI, is a mouse cursor.

The specific implementation will depend on your game, but it’s useful to remember that the mouse cursor might have different states, and different sizes for many resolutions of the PC game.

What looks clickable, should be clickable

If you have UI elements in PC UI that look like they’re clickable – they should be clickable.

Great example of it is Media Player App from Watch Dogs 2 PC: every tab, every button is clickable and have functionality.

If you’re developing the game for the consoles first and use the gamepad prompts, for PC, they should be converted into the clickable buttons (and make sure that your UI clearly indicates what is clickable button, and what is not).

As you can see from Watch Dogs 2 PC example, the player can clearly see what is button, and what is just hint.

What is clickable, should have mouse over state

All clickable elements should also have mouse over state (which in many cases is an additional, third state between default and selected).

Mouse is a subtle device

Speaking about less obvious things, keep in mind that expected feedback from the mouse interaction is different than similar gamepad feedback.

When you select something with the gamepad, you have very clear and distinct, “physical” actions. The mouse is much more subtle device, and if you combine it with usually very intense visual feedback from the gamepad selection, such UI may feel wrong on the interaction level.

Tone down the feedback intensity for the mouse.

Mouse is fast and precise device

Here, you can see how the PC player’s expectations from mouse-controlled shooting mechanic looks like (with some gamepad players on the background :)).

The mouse is fast and precise device, so many usual aiming assists for gamepad can ruin the expected feeling of high responsiveness from the mouse.

There shouldn‘t be extra obstacles between the mouse move and the character‘s reactions.

You can learn more about aiming and aim assists, and how to look at them from the Human-Computer Interaction perspective in my other article Building Character Feel in a First Person Game.

Differences and impact of the mouse controls can be pretty big. Watch Dogs 2 PC, for example, had different camera settings and some changes to the animation system (rotation speed in aiming mode had to be much faster with the mouse).

It also had an impact on the gameplay: we noticed on playtests, that many PC players were much more eager to engage in firefights, as shooting mechanic with the mouse was much more satisfying than with the gamepad (they did less driving though).

Keyboard IS NOT Gamepad

The next thing after the mouse that I’d like to talk about is how to properly match the gamepad controls layout to the keyboard layout, and why keyboard is not gamepad.

One of the common mistakes that I often see in bad PC ports is when the gamepad button just directly assigned to the keyboard, without taking into account how the whole controls layout will work with the keyboard. You should design separate layouts for the keyboard and the gamepad, taking into account properties of each device.

You can learn more about game controls design in my other article.

Myth of “many buttons”

There’s a common misconception that the keyboard has “many buttons” compared to the gamepad. It’s not.

Essentially, you have [WASD] plus buttons around it. At the first glance, it’s still more than the gamepad, but PC player expectations are different.

Don’t use joint actions on PC

In complex AAA console games, due to gamepad limitations we can often see joint actions: the same button does one action after “press”, second action after “hold”, third action in different context and so on. Such mechanics are used pretty often, and it became standard convention on the consoles.

On PC, players expect separate actions that can also be remapped(!).

One action ->One button (Re-mappable)

Think early about controls customization

Speaking of re-mapping. This is one of the most technically complicated PC-specific features. And if you want to avoid the huge number of bugs, define what is re-mappable as early as possible. Define, how the re-mapping flow will work, how you prevent the player’s mistakes, how the UI screen is designed and so on.

Take into account different contexts

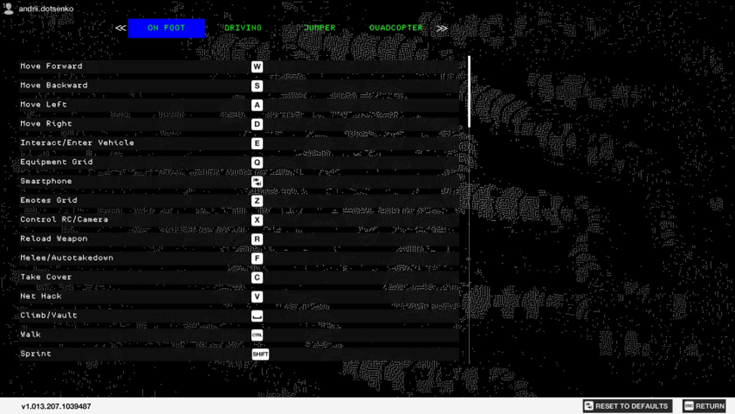

In addition to re-mapping, your game might have a lot of different contexts. For example, Watch Dogs 2 had: On Foot, Driving, Drone, mission-specific controls, game mode-specific controls, side activity-specific controls, etc.

On PC, you cannot just turn off some actions, the same way it works with non-remappable gamepad controls – you need to take into account, that all the controls can be changed (you should also consider making your gamepad controls re-mappable, it’ll be a great addition to the accessibility options of your game).

The mouse is also re-mappable

Mouse is also re-mappable, including additional buttons and even the mouse wheel.

And even more, some players can assign quite keyboard-specific actions on the mouse. For example, some Far Cry 4 players used mouse buttons for running forward and jumping, and [Space] on the keyboard for shooting.

Also, consider blocking the player’s ability to assign the mouse wheel on certain actions (especially, if your game is competitive), as there are plenty of ways to use it as an exploit/cheating, like quickly shooting from a single fire weapon, or generally pressing some buttons much faster than it’s intended by design.

Mouse vs Keyboard

The mouse and keyboard are related: as the mouse is the default way of interaction, the keyboard is much faster, but harder to learn.

The approach that was used in Watch Dogs 2 PC is “mouse for learning, keyboard for speed and mastery”, when UI screens are designed for the mouse by default, but the player can learn the keyboard shortcuts during mouse interaction with the UI.

For example, you could learn all the keyboard shortcuts for weapons, equipment and mass hacks, interacting with the Equipment Grid with the mouse.

You still have the gamepad on PC!

Finishing the mouse and keyboard topic, it’s worth to mention that you still have the gamepad! Usually, different models of Xbox or XInput controllers, but in the recent years, PlayStation controllers got better support on PC as well.

Which means, that some PC players might have more than one gamepad connected simultaneously, and it’s good to indicate it in UI, if the player has different gamepad types connected.

Don’t forget about tutorials!

And one little thing to finish with PC controls: remember about tutorials! In case of multi-platform AAA game, we may work on tutorials on the pretty late development stage, and often don’t have time to adapt them for PC properly. Thinking about PC tutorials in advance, and spending some extra efforts for proper adaptation can contribute a lot to the experience that your game was created with PC audience in mind.

You might need:

- Different text descriptions for the mouse & keyboard/gamepad.

- Different illustrations/videos depending on the active input device.

- Loading tips that can be specific for a certain type of controls.

- All these UI elements should support input auto-switching and change on-the-fly depending on the current control device.

For example, for Watch Dogs 2 tutorials and skill tree on PC had additional screens, descriptions and separate videos for the mouse & keyboard controls.

Managing PC players expectations

Let’s move to the second part of my article, to video options and performance. Here, I’d like to look at this topic through the lens of the PC audience expectations, and how to meet these expectations.

Common PC configurations

There’s a wide variety of PC configurations, and it’s almost impossible to cover them all, but based on the data and some of my previous research, there are certain patterns of how players build and upgrade their PCs.

Base hardware age of the desktop PC configurations usually breaks down the following way:

- Current Gen CPU, 1-2 years old, ~1/2 of them have the newest gen GPU – [~30% of the audience]

- Previous Gen CPU, 2-3 years old, ~1/2 of them have GPU from the newer gen than CPU – [~30% of the audience]

- Old Gen CPU, 3-5 years old, ~1/4 of them have GPU from the newer gen than CPU – [~40% of the audience]

Desktop PC players have a lot of unbalanced configurations with a combination like “old CPU + newer GPU”, with the GPU as the main contributor to the performance expectations. Unfortunately, this leads to a situation when in ~30-40% of cases, the graphics/performance will be below the player’s expectations.

~15% of PC AAA game players are notebook users: ~40% current gen (1-2 years old), ~50% previous gen (2-3 years old), ~10% old gen (3-5 years old). Notebook configurations are usually more balanced performance-wise as RAM is often the only upgradeable part.

AAA games on PC are primarily played on Intel and NVIDIA machines (65% of Intel and 75% of NVIDIA, according to the latest Steam Hardware Survey, but keep in mind that it also includes a lot of weaker machines, high-end PC segment is usually skewed towards Intel/NVIDIA even more).

What also changed in the recent years is that the majority of PC players will at least own a gamepad (usually, Xbox/XInput kind).

Three most vocal groups of PC players

There are three most active player groups in performance-related discussions (with a caveat that we’re speaking about big AAA game on PC):

- Low-end PC segment: “I want to run it on my potato PC (30 FPS)”, up to ~40% of the audience, or even more in case of good low preset, 4+ years old CPU setup.

- High-end PC segment: “It should run 60 FPS+ on Ultra on my new fancy GPU” ~50% of the audience, 2-3 years old CPU setup.

- Hardware enthusiasts: “It should run 60 FPS+ in the highest resolution possible on my top-notch setup” ~10% of the audience, the latest setup money can buy.

Lets’s look at them in more details.

Low-end PC Segment (~40% of the audience, 4+ years old CPU setup)

“I want to run it on my potato PC (30 FPS)”

So, what can we say about low-end segment? It’s a weak, old hardware or notebooks.

The main wish of these people is just to run your game in some playable state.

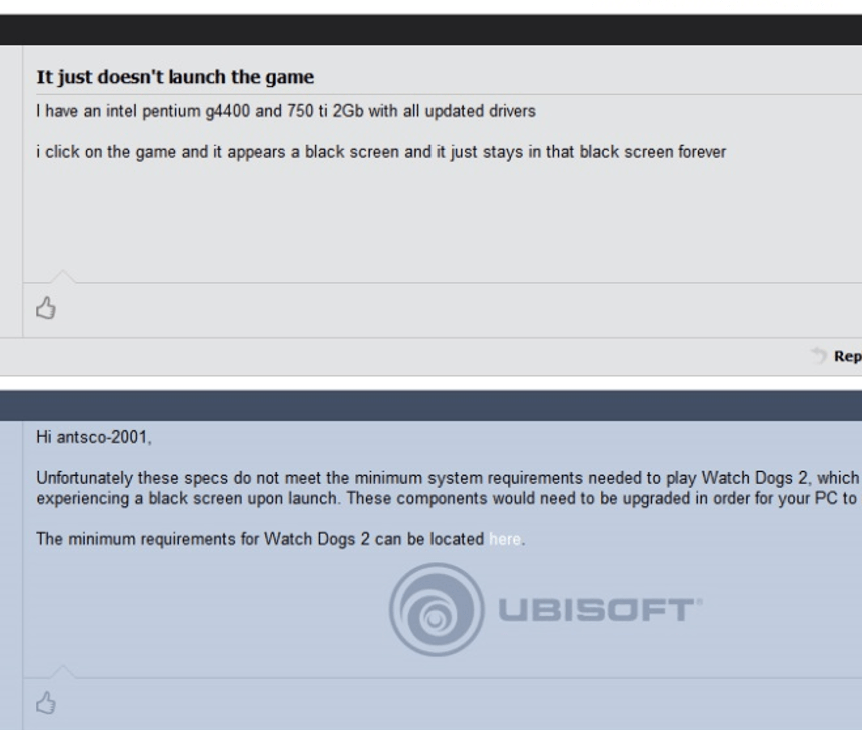

Usually, they do not trust minimal requirements, and will be trying to launch your game on the wide variety of old and, sometimes, unexpected devices (seriously, some people even tried to launch Watch Dogs 2 on Intel Compute Stick!).

Low preset is quite challenging from the content adaptation and CPU side:

- CPU load is hard to scale (you should do it on the early stage).

- Low preset may require a separate pack of content (see Overwatch).

- Things like NVIDIA DLSS may also help with the performance.

But.

There are many of them.

Despite all the challenges, this part of the PC audience is potentially huge, it just contains a lot of 3-5+ years old builds, integrated GPUs, notebooks, etc.

For example, for the original Overwatch, Blizzard has invested a significant amount of efforts to support integrated Intel GPUs and even made a separate low-preset content pack for the game levels. As a result, there was ~22% of Overwatch players who used integrated graphics/played on notebooks (2017 data).

High-end PC Segment (~50% of the audience, 2-3 years old CPU setup)

“It should run 60 FPS+ on Ultra on my new fancy GPU”

In case of AAA-game, the high-end segment expectations are really high. The main issue here is that the primary contributor to the performance expectations is GPU.

Basically, these players expect that after they purchased new GPU, all new games should work great. Which is often not the case in reality, and leads to a big gap between real and expected performance.

Problem is – these people is the most active part of the audience who basically defines user score of your game. And when they’re upset, it hurts!

It also hurts on ALL the platforms. There’s a pattern for the multi-platform games, which shows that the bad PC version hurts user score for other platforms as well. Good PC version doesn’t have any impact on score, though.

I played Mafia 3 on PC, and it wasn’t THAT bad as it’s user score, but the way it was presented to the high-end PC segment (with 30 FPS lock and unpolished mouse & keyboard controls) was unacceptable for them and also had impact on the overall score for other platforms.

If you read PC forums, you might get an impression that it’s a pretty toxic place with completely unrealistic demands to the developers. But what do these players actually want?

The main problem that high-end PC players are usually trying to solve in performance-related threads is “how to launch the game with all the fancy effects, but still have good framerate?”

So here it is, the main wish of the PC audience:

The game that looks significantly better than the console version/similar console game but has a good performance on ~$300-400 price range GPU

Why this price range? It feels like this is the amount of money PC players usually willing to spend on a new GPU. In most cases, GPU in this price range is *technically* more powerful than the console, and people expect better image quality, even if their overall PC build is not quite capable of it.

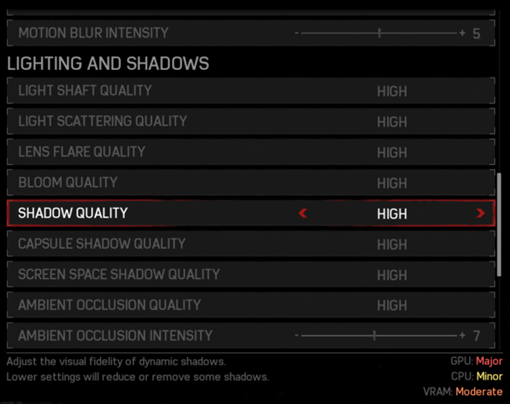

There’s no easy answer to this wish, outside of day-to-day focus on the PC version performance throughout all the project lifecycle, but one of the ways to address this problem is creating of a cost-effective “Ultra” preset.

This might include performance-cheap version of advanced render features (for example, in Watch Dogs 2 PC we’ve added a cheaper version of the screen space reflections, and more efficient version of temporal anti-aliasing), and some focus on decreasing of CPU/RAM usage to better support of “Old PC + New GPU” cases.

Another question from the high-end PC segment is:

“What FPS will I have on my PC with [X] settings?”

There’s a set of features that help to answer this question, most of them are aimed to inform the player better about the game’s performance on a given PC setup:

- System requirements communication – be very clear and highlight potentially critical components (e.g. if your game, for example, requires certain CPU features in order to work, say about it very clearly). Also, communicate what is the target FPS of your system requirements (e.g. 30 or 60) – if you don’t do this, the PC players will expect that these are recommendation for 60 FPS (or more :)).

- Improved feedback – it can be VRAM usage bar, preview pictures for different levels of graphics quality, performance impact indicators for each options, or just more detailed option descriptions.

- The Benchmark – the ultimate way to improve the performance feedback. There’s a set of best practices for the graphical benchmark design I found useful, let’s look at them in more details.

The Benchmark is a short scene that “sells” the game graphics to the player and shows expected game’s performance on the current settings.

- Ideally, it should be short, no more than 60-90 seconds long.

- It should show relevant FPS (so design your benchmark scene carefully).

- It should be beautiful and “sell” the game graphics, as it might be the first time the PC player actually sees the game graphics (get some help from artists, don’t just use your internal performance benchmark scene).

Combination of these three factors makes the benchmark shareable, with the players showing off the performance of their new rig.

Hardware Enthusiasts (~10% of the audience, the latest setup money can buy)

“It should run 60 FPS+ in the highest resolution possible on my top-notch setup”

Hardware enthusiasts want the best experience possible and will try to run your game on some monster PCs, with ridiculous resolutions, on exotic multi-GPU and multi-monitor setups.

There are not many of them, but what’s important about enthusiasts is that they’re very active as a community. They’re often bloggers, journalists, or some specialised communities like WSGF, and if your game has special features for enthusiasts – they’ll talk about it more.

For example, Watch Dogs 2 PC got two “gold” and two “silver” awards from WSGF (Widen Screen Gaming Forum) – you can see more detailed evaluation here.

Let’s look at some example of enthusiast features from Watch Dogs 2 PC.

The main insight from Watch Dogs 2 PC 4K adaptation, is that the high screen resolution requires high content resolution to shine (which includes UI art that can be scaled up, by the way).

The first case is Ultra Textures.

The effect of high-resolution textures is pretty subtle on 1080p, but 4K resolution multiplies this effect significantly. 4K resolution was one of the main reasons why some players asked us for high definition textures support.

The second case is what’s called Extra Details in the Watch Dogs 2 PC Video Options.

It’s a pretty straightforward option – we just show better LODs (far and near).

Such kind of settings is not very reasonable for 1080p (you’ll get horrible aliasing), and it’s performance-heavy (5-15 fps cost), but when you combine it with 4K (or even 2K) resolution, the game looks stunning.

We had some players who set 4K resolution and max setting for Extra Details, and just walked San Francisco streets, without even playing the game.

Here’s Watch Dogs 2 PC default High (console) quality preset in 1080p.

And this is 4K with Ultra settings and Extra Details: more details, better textures, shadows and lighting (and it can be even better – this is the maximum settings my hardware could handle to make a screenshot).

Also, thanks to enthusiast features, even 2-3 years after release, your game may still have what to offer in terms of the graphics quality. Combined with a long post-launch period with a lot of fixes and additional content, it creates a great foundation for back catalogue performance.

The good game on PC is still the good game after 5 years, after 10 years. If the lifecycle of your game has already ended on the console, people can continue playing it on PC for a very long time.

Some companies even built the whole business on top of it!

Some extra things to finish

And some other minor things that should be mentioned about PC community.

Give them tools!

PC community is also more active in general.

At some point, Watch Dogs 2 had a contest for the best screenshot. And PC players were the second platform by the number of screenshots submitted, having significantly less players overall.

And that’s why is so important to have tools which support higher activity level of PC community. We got a lot of cool stuff from the PC community by having features like NVIDIA Ansel. Give PC players tools to create and share their own stories.

They will ask you for this

The last thing that I’d like to talk about is minor features. If you work on a big game, by addressing a minor feature the community asked you for, you can make happy thousands of players.

For example, advanced display features like FOV slider or FPS limiter are used by approximately 10% of PC players. Many of such features are pretty basic, and not very expensive to implement (and the same is true for many accessibility features, especially if you think about them in advance).